In January of 2003 the CEO of I/O let the company know that he was leaving to join Halliburton. That made working for the company much less attractive to me.

Around the same time a headhunter started calling me asking if I would be interested in joining a small software company that was recently created out of an industry sponsored consortium. I think my first interview was in December of 2002 I finally received an offer in May of 2003.

I started the job June 1, 2003. OpenSpirit had 18 employees at the time, and under $2 million in sales. Our cash position was precarious, and I was brought in to try and take this company to a stage where we could sell it.

The Company was dedicated to upstream (that is, exploration and production), subsurface (that is, seismic data and interpretations, well log data and interpretations, and other information associated with the view of the earth model), middleware (software that performs operations between data and applications. Think of plumbing.) Our clients were mostly the Information Technology and Data Management departments in the oil companies. The users were mostly geologists and geophysicists.

My first day on the job was in Stavanger, Norway. The EAGE (European Association of Geoscientists and Engineers) convention was being held there. We also had a user forum in town. It was an eye opening experience. The team was good, but the clients had many, many issues with the software. (Most of it focused on the speed of the operation and what sort of data the application move)

The company was funded with a reasonable amount of capital for the market size. There were a couple of other companies that were started at the same time with similar goals (Trade Ranger and PetroCosm were the two biggest. They each had investments of about $100 million each. We had, to this point, about $4.5 million)who crashed and burned well before I even started with OpenSpirit.

The Company was funded by Schlumberger Technology Company, Shell Technology Ventures, and Chevron Technology Ventures. Later, we added Paradigm Geophysical as a balancing partner to Schlumberger.

We did go through several small rounds of capital before we brought in a large round when Paradigm joined. In a small company like this, cash was always the problem that was hanging over your head. It didn't really help that nobody in the company has any experience working for a start-up. I would have company meetings regularly where I would express my discomfort at the state of our Balance Sheet. I found no commiseration. But by virtue of the fact that we were small and lean, we were able to make money for almost every year I was running the company.

We grew pretty strongly in the middle years of my tenure. We had a good team, though at times rather dysfunctional. I won't go into the details, but suffice it to say that management was fired, management quit, and the company survived in spite of both events. (de mortuis nil nisi bonum).

The decision to sell the company, and the process we went through deserve their own post.

Sunday, June 26, 2011

Friday, June 24, 2011

Input/Output: My life in manufacturing

You may have noticed a theme in most of my jobs to this point. The only company that actually made anything was Exxon. (S/N notwithstanding).

But now I was about to embark on a new branch of my career. I/O (now called Ion, if you are at all interested. Or maybe Inova, depending on what part of the company you are looking at) made stuff. We made seismic acquisition stuff. Geophones, Hydrophones, Seismic Cables, Land Acquisition Systems, Vibrator Trucks (not as sexy as their name implies), and everything to support the acquisition of seismic data.

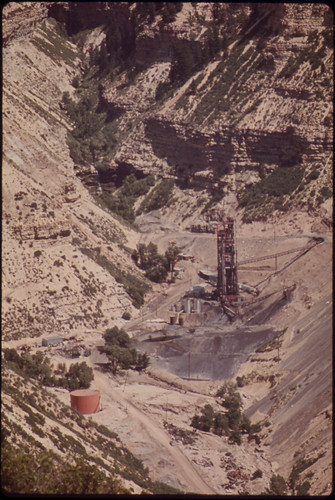

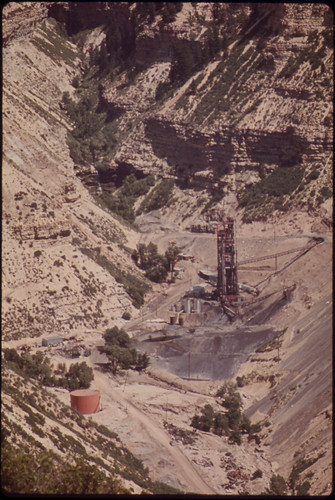

Collecting seismic data is really doing nothing more than recording sound. Granted, you are recording sound from thousands of different sources located either on the trackless ocean or buried in the ground over many square miles, and then the sound waves need to be reconstructed so you can see what they bounced off of, many thousands of feet underground. (crazy stuff. The largest Seismic Vessels now (from PGS, thank you very much) can tow as many as 22 streamer cables, each about 8 km long. They are the largest man made moving things on earth). You can imagine that you need to know exactly where those geophones are located, and when, exactly you deploy the "source" of the sound waves (either explosives like dynamite or the vibe trucks mentioned above). It is complicated.

I was hired to run the Land Data Systems group. We were responsible for the new digital "geophone" (actually a MEMS accelerometer) the Central System, which is the computer that keeps track of where all the data is coming from and then puts it all in the right place, and the sales thereof.

It was a hard time in the oil business, and not many oil companies were collecting land data. And not many service companies were buying new seismic equipment. But we had a net technology (Vectorseis is what we called it) and were sort of effective. I had to cut my staff from over 160 people to under 70 people (which was not fun), outsource some manufacturing, and try and learn about things like "Long Lead Time Items" and "Inventory". Neither of these were too important (or even existed!) in the software or data world.

I had a good time learning these things. I would walk around our factory floor and pick things up (which you can't do with software) just to hold in my hand something I made.

We did pretty well considering the environment. We increases sales in the year I was there from about $3 million a quarter to about $8 million a quarter.

But soon enough some headhunters came calling. I was destined to get back into software. I worked for I/O for 14 months. There was such a strong culture there (and such a great CEO, who quit before I did) that I still consider myself an I/O Alumni.

But now I was about to embark on a new branch of my career. I/O (now called Ion, if you are at all interested. Or maybe Inova, depending on what part of the company you are looking at) made stuff. We made seismic acquisition stuff. Geophones, Hydrophones, Seismic Cables, Land Acquisition Systems, Vibrator Trucks (not as sexy as their name implies), and everything to support the acquisition of seismic data.

Collecting seismic data is really doing nothing more than recording sound. Granted, you are recording sound from thousands of different sources located either on the trackless ocean or buried in the ground over many square miles, and then the sound waves need to be reconstructed so you can see what they bounced off of, many thousands of feet underground. (crazy stuff. The largest Seismic Vessels now (from PGS, thank you very much) can tow as many as 22 streamer cables, each about 8 km long. They are the largest man made moving things on earth). You can imagine that you need to know exactly where those geophones are located, and when, exactly you deploy the "source" of the sound waves (either explosives like dynamite or the vibe trucks mentioned above). It is complicated.

I was hired to run the Land Data Systems group. We were responsible for the new digital "geophone" (actually a MEMS accelerometer) the Central System, which is the computer that keeps track of where all the data is coming from and then puts it all in the right place, and the sales thereof.

It was a hard time in the oil business, and not many oil companies were collecting land data. And not many service companies were buying new seismic equipment. But we had a net technology (Vectorseis is what we called it) and were sort of effective. I had to cut my staff from over 160 people to under 70 people (which was not fun), outsource some manufacturing, and try and learn about things like "Long Lead Time Items" and "Inventory". Neither of these were too important (or even existed!) in the software or data world.

I had a good time learning these things. I would walk around our factory floor and pick things up (which you can't do with software) just to hold in my hand something I made.

We did pretty well considering the environment. We increases sales in the year I was there from about $3 million a quarter to about $8 million a quarter.

But soon enough some headhunters came calling. I was destined to get back into software. I worked for I/O for 14 months. There was such a strong culture there (and such a great CEO, who quit before I did) that I still consider myself an I/O Alumni.

Tuesday, June 14, 2011

Post Bankruptcy. A New Beginning

I am very happy to say that Bell Geospace was able to exit bankruptcy. I was an active participant in most of the proceedings, but I finally decided that it would be best if I passed the reigns on to the new president. He finished the job admirably, with one of our investors. I am also happy to say that the Company is surviving, even thriving, today.

After leaving BGI, my fiancee and I decided to take a break, and left the country for several months. While not technically a job, that trip is still a big part of why I am where I am today. It gives one plenty of perspective to take some time off and spend some time in beautiful places with someone you love. It focuses the mind strongly on what is, and what isn't important.

I use to have a website with photos and stories from that trip. But I used GeoCities,so it is all gone. I tried to capture most of the to blogger, but it is cumbersome. You can see the posts here, with a little work.

When we returned to the US, I took a couple of years where I consulted and generally enjoyed myself.

But all good things had to come to an end.

I made a small investment with a friend into a company that made solid streamer cables for seismic data acquisition. (The company originally had its manufacturing done in Mineral Wells. My friend had his own airplane, and to try and convince me to make an investment, he flew me and another friend up there from Houston. On take-off on our way home, he lost an engine. (luckily it had two). Funny way to try and raise money.)

We sold this company to Input/Output. They offered me a job as the Business Unit Manager of their Land Seismic Systems division. That was certainly a new thing for me, and it set me on a new and interesting path.

After leaving BGI, my fiancee and I decided to take a break, and left the country for several months. While not technically a job, that trip is still a big part of why I am where I am today. It gives one plenty of perspective to take some time off and spend some time in beautiful places with someone you love. It focuses the mind strongly on what is, and what isn't important.

I use to have a website with photos and stories from that trip. But I used GeoCities,so it is all gone. I tried to capture most of the to blogger, but it is cumbersome. You can see the posts here, with a little work.

When we returned to the US, I took a couple of years where I consulted and generally enjoyed myself.

But all good things had to come to an end.

I made a small investment with a friend into a company that made solid streamer cables for seismic data acquisition. (The company originally had its manufacturing done in Mineral Wells. My friend had his own airplane, and to try and convince me to make an investment, he flew me and another friend up there from Houston. On take-off on our way home, he lost an engine. (luckily it had two). Funny way to try and raise money.)

We sold this company to Input/Output. They offered me a job as the Business Unit Manager of their Land Seismic Systems division. That was certainly a new thing for me, and it set me on a new and interesting path.

Wednesday, May 4, 2011

Bankruptcy, and other learing experiences

In July of 1999, the Board of Directors of Bell Geospace asked me if I would be willing to take over at President and CEO. This was a hard decision. The guy I would be replacing was (and is) a friend of mine. And the Company was in a tight spot.

In spite of raising over $20 million in equity and $14 million in debt we were quickly running out of cash. We had to close several sales or an additional round of funding to make the company work.

Reluctantly, I said yes.

The Board put me into the role and I immediately had to hire a CFO. I ended up hiring a fellow who became a very close friend (battle scars). I kept telling him we had plenty of cash (well over a million dollars) but he never really asked how much we were spending. Alas, we were spending WAY too much.

So first we tried to raise more money. We had a term sheet from a young and up and coming Private Equity firm based in Lime Rock, CT. The problem was the "pre-money" valuation (that is, what share price they were willing to pay for our stock) was $12 million. Yipes! Our last "post-money" (after our last round of funding) valuation was $45 million. That was quite a "down round". None of the current investors were willing to see such dilution.

So we focused on sales. We really had a pretty spectacular growth rate - in 1998 we sold only about $200k worth of data, and in 1999 we sold over $2 million! But our burn rate (cash out minus cash in) was about $2.5 million a month. Yipes!

My CFO told me that we had to get relief from our debt obligations, or we would be in violation of our loan covenants. (you had to keep a certain amount of cash or the loan could be called. There were many of these types of rules we had to follow)

Our biggest debtor (other than the loan with Third Coast Capital) was with Lockheed Martin, the manufacturer of the instrument we were using to collect our data. We had a payment due in October, and if we paid it, all our loans would be called.

It seemed like it would be a simple thing to go to Lockheed and ask that we reschedule payments. (there is a lot of history that I am leaving out here. The instrument we had was delivered very late, which meant that we missed the oil price peak, which meant that oil companies were cutting back on exploration, which meant that nobody wanted to buy our data. For want of a nail...)

But nothing with a large government contractor is ever simple.

This division of Lockheed we were dealing with (Lockheed Martin Federal Systems - they also made submarines) had never had a private client before. They were so naive that when it was obvious that they were not going to make the contracted date for delivery of one of our instruments, they told us that the price was going up (!!). We pointed out that in the contract, if they missed delivery, they had to pay a penalty. They said it never worked that way with the government. (I guess!)

So my CFO and I showed up in Manassas, Virginia on September 30, 1999. We had a meeting arranged with the head of the division, her finance guy, and a bunch of other people who didn't talk.

The meeting did not start off too well. She started telling us how they needed our cash in order to make their yearly bonus. I explained that we would not be able to pay them, and we were looking for a payment plan where we could push the payment out into 2000. She was not eager to do that.

Every time I explained that we could not pay, she explained that they needed our cash so they could get their bonus. I then brought up the fact that we were in this predicament because of their inability to deliver the instrument on time. She apologized, and then told me that she needed our cash to make their bonus.

I said that if we did not get relief, we would have to file for bankruptcy. She said that didn't matter to her, as long as she got her cash.

This meeting lasted pretty long into the evening. I was getting frustrated, and I could tell she was also.

I finally said, if you do not give me a payment plan, I am going to file for bankruptcy in the morning. She said "Well, you have to do what you have to do, and so do I. I need that cash"

So I got up to leave and said we were filing as soon as the courts opened. She said OK, and then turned to one of her minions and asked, "What does "filing for bankruptcy" mean, anyway?"

I was sort of flabbergasted. I said:

"It means you won't be getting your bonus"

We filed in the morning.

In spite of raising over $20 million in equity and $14 million in debt we were quickly running out of cash. We had to close several sales or an additional round of funding to make the company work.

Reluctantly, I said yes.

The Board put me into the role and I immediately had to hire a CFO. I ended up hiring a fellow who became a very close friend (battle scars). I kept telling him we had plenty of cash (well over a million dollars) but he never really asked how much we were spending. Alas, we were spending WAY too much.

So first we tried to raise more money. We had a term sheet from a young and up and coming Private Equity firm based in Lime Rock, CT. The problem was the "pre-money" valuation (that is, what share price they were willing to pay for our stock) was $12 million. Yipes! Our last "post-money" (after our last round of funding) valuation was $45 million. That was quite a "down round". None of the current investors were willing to see such dilution.

So we focused on sales. We really had a pretty spectacular growth rate - in 1998 we sold only about $200k worth of data, and in 1999 we sold over $2 million! But our burn rate (cash out minus cash in) was about $2.5 million a month. Yipes!

My CFO told me that we had to get relief from our debt obligations, or we would be in violation of our loan covenants. (you had to keep a certain amount of cash or the loan could be called. There were many of these types of rules we had to follow)

Our biggest debtor (other than the loan with Third Coast Capital) was with Lockheed Martin, the manufacturer of the instrument we were using to collect our data. We had a payment due in October, and if we paid it, all our loans would be called.

It seemed like it would be a simple thing to go to Lockheed and ask that we reschedule payments. (there is a lot of history that I am leaving out here. The instrument we had was delivered very late, which meant that we missed the oil price peak, which meant that oil companies were cutting back on exploration, which meant that nobody wanted to buy our data. For want of a nail...)

But nothing with a large government contractor is ever simple.

This division of Lockheed we were dealing with (Lockheed Martin Federal Systems - they also made submarines) had never had a private client before. They were so naive that when it was obvious that they were not going to make the contracted date for delivery of one of our instruments, they told us that the price was going up (!!). We pointed out that in the contract, if they missed delivery, they had to pay a penalty. They said it never worked that way with the government. (I guess!)

So my CFO and I showed up in Manassas, Virginia on September 30, 1999. We had a meeting arranged with the head of the division, her finance guy, and a bunch of other people who didn't talk.

The meeting did not start off too well. She started telling us how they needed our cash in order to make their yearly bonus. I explained that we would not be able to pay them, and we were looking for a payment plan where we could push the payment out into 2000. She was not eager to do that.

Every time I explained that we could not pay, she explained that they needed our cash so they could get their bonus. I then brought up the fact that we were in this predicament because of their inability to deliver the instrument on time. She apologized, and then told me that she needed our cash to make their bonus.

I said that if we did not get relief, we would have to file for bankruptcy. She said that didn't matter to her, as long as she got her cash.

This meeting lasted pretty long into the evening. I was getting frustrated, and I could tell she was also.

I finally said, if you do not give me a payment plan, I am going to file for bankruptcy in the morning. She said "Well, you have to do what you have to do, and so do I. I need that cash"

So I got up to leave and said we were filing as soon as the courts opened. She said OK, and then turned to one of her minions and asked, "What does "filing for bankruptcy" mean, anyway?"

I was sort of flabbergasted. I said:

"It means you won't be getting your bonus"

We filed in the morning.

Friday, April 22, 2011

Bell Geospace

I returned to the US, bought a house in the Houston Heights, and decided that I would not work for a while.

Due to personal circumstances beyond the scope of this blog, that didn't happen. So when my old boss from Landmark called me and said he was recruited to run a start-up data company, I said yes.

The company, Bell Geospace, had secured the rights to an instrument invented for stealth submarine navigation - a Gravity Gradiometer. It was about the coolest thing I had ever seen: ;

;

Due to personal circumstances beyond the scope of this blog, that didn't happen. So when my old boss from Landmark called me and said he was recruited to run a start-up data company, I said yes.

The company, Bell Geospace, had secured the rights to an instrument invented for stealth submarine navigation - a Gravity Gradiometer. It was about the coolest thing I had ever seen:

;

;It was designed to measure the first dervivative of gravity. Now, since we all know that gravity is a vector, so the first derivative of a vector is a nine component tensor. We also know that because of self similarity (the xy component is equal to the yx component, etc) there are only five unique components of that nine component tensor.

But more to the point, the instrument (which we dubbed the "FTG" or Full Tensor Gradiometer (yes, I came up with that. Just as I did Full Wave Seismic.)) had to measure the difference in gravity between two points about five inches apart.

Concede that it did, and let me get on with the story.

We knew that there was great potential for this data. If you could find a way to combine this information with seismic data, you could make the seismic data much more valuable. Indeed, if you could combine this data with seismic data during processing, it would be possible to determing the size, shape, and thickness of subsurface salt bodies. That is important because salt is impervious to oil and gas, and does a good job trapping it. But salt is also a great reflector of sounds waves (for seismic imaging) so it hard to "see" through.

We decided that to make this company successful, we needed to go all in, all the way. So I started as the VP of Sales, but quickly took over at Chief Operating Officer. In that roll we raised a bunch of money, hired a lot of people, bought (and sank) a boat, opened an overseas office, chartered a couple of boats (that didn't sink) and generally had a grand old time.

Our problem, as with many small companies, was that our sales did not come close to keeping up with our expenditures. We hired over 60 people any never had more that $2 million a year in sales. We were burning (ie, spending more than we were taking in) about $1.5 million a month. We were cursed with cash. We had a CEO, a COO, a CFO (and a controller), an Ops Manager, two or three salesmen, an overseas office, and a charter on two big boats. (I won't go into the vessel that sank. It was a SWATH [small waterplane area twin hull] vessel originally designed as a fishing boat. We made mistakes)

We had great plans, great marketing, it is just that the industry was not ready for us. Then oil dropped to about $9/bbl (those bad old days) and the demand dried up as well.

As we were running out of cash, the Board of Directors asked me if I would take over as CEO. (remember, the previous CEO was (and is) a good friend of mine) I said OK, but prepared them for the fact that we might have to file for bankruptcy.

They were prepared, I was promoted, and we finally filed for Chapter 11 protection. I think that is worth its own entry.

But more to the point, the instrument (which we dubbed the "FTG" or Full Tensor Gradiometer (yes, I came up with that. Just as I did Full Wave Seismic.)) had to measure the difference in gravity between two points about five inches apart.

Concede that it did, and let me get on with the story.

We knew that there was great potential for this data. If you could find a way to combine this information with seismic data, you could make the seismic data much more valuable. Indeed, if you could combine this data with seismic data during processing, it would be possible to determing the size, shape, and thickness of subsurface salt bodies. That is important because salt is impervious to oil and gas, and does a good job trapping it. But salt is also a great reflector of sounds waves (for seismic imaging) so it hard to "see" through.

We decided that to make this company successful, we needed to go all in, all the way. So I started as the VP of Sales, but quickly took over at Chief Operating Officer. In that roll we raised a bunch of money, hired a lot of people, bought (and sank) a boat, opened an overseas office, chartered a couple of boats (that didn't sink) and generally had a grand old time.

Our problem, as with many small companies, was that our sales did not come close to keeping up with our expenditures. We hired over 60 people any never had more that $2 million a year in sales. We were burning (ie, spending more than we were taking in) about $1.5 million a month. We were cursed with cash. We had a CEO, a COO, a CFO (and a controller), an Ops Manager, two or three salesmen, an overseas office, and a charter on two big boats. (I won't go into the vessel that sank. It was a SWATH [small waterplane area twin hull] vessel originally designed as a fishing boat. We made mistakes)

We had great plans, great marketing, it is just that the industry was not ready for us. Then oil dropped to about $9/bbl (those bad old days) and the demand dried up as well.

As we were running out of cash, the Board of Directors asked me if I would take over as CEO. (remember, the previous CEO was (and is) a good friend of mine) I said OK, but prepared them for the fact that we might have to file for bankruptcy.

They were prepared, I was promoted, and we finally filed for Chapter 11 protection. I think that is worth its own entry.

Saturday, April 9, 2011

Cashed out and sent home. An intermission

After Landmark was purchased by Halliburton, I decided it was time to return to the US and try something new.

First, I had to find my replacement for Halliburton. I identified the regional manager for IBM, and recruited him pretty hard. This turned out to be the best thing that ever happened to him. He reluctantly took the job, and we overlapped for a short while.

Here is a funny anecdote: Landmark, and now Halliburton, had quarterly sales meetings where the regional VPs would get together with our boss and thrash out what the following quarter's sales goals would be. As you can imagine, this was always an interesting give and take, because we were a public company that gave regular guidance to the stock market. The VPs pushed for as low a number that was acceptable, our boss (and the CEO) always pushed for the highest number possible.

In my last QSOR (Quarterly Sales and Operations Report) I was accompanied by my successor. But since he was so new, I was the one who made the presentation. SO I got up in front of the group, and pitched what I thought was a fair number.

At this point, my boss (who looked and acted like a high school football coach) said that I was sandbagging, and that the number I presented was too low. He knew that I was leaving the company very, very soon.

So I just looked at the new VP (who had just flown in from Kuala Lumpur) and said, "OK Hank (my boss), what do you want it to be?" he gave me a number something like 20% higher than mine. I smiled and said "I am sure that Koid (my successor) will have no problem hitting that number"

I am not sure what Koid thought, but that was his new target.

We had fun at these quarterly meetings. We introduced new selling techniques, new products, new marketing plans.

One other story from my last QSOR is that my boss asked who would like to introduce the marketing VP to the group. Nobody seemed too interested, so in the interest of fun, I volunteered to do so. She was so upset that right before I got on stage she came and asked me, sotto voce to please not embarrass her. Of course I did not. I gave a great introduction, stressing the importance of Marketing to the company (which I honestly believe, to this day)

Then I came home, took a couple of months off, and started with a brand new company.

That's up next.

First, I had to find my replacement for Halliburton. I identified the regional manager for IBM, and recruited him pretty hard. This turned out to be the best thing that ever happened to him. He reluctantly took the job, and we overlapped for a short while.

Here is a funny anecdote: Landmark, and now Halliburton, had quarterly sales meetings where the regional VPs would get together with our boss and thrash out what the following quarter's sales goals would be. As you can imagine, this was always an interesting give and take, because we were a public company that gave regular guidance to the stock market. The VPs pushed for as low a number that was acceptable, our boss (and the CEO) always pushed for the highest number possible.

In my last QSOR (Quarterly Sales and Operations Report) I was accompanied by my successor. But since he was so new, I was the one who made the presentation. SO I got up in front of the group, and pitched what I thought was a fair number.

At this point, my boss (who looked and acted like a high school football coach) said that I was sandbagging, and that the number I presented was too low. He knew that I was leaving the company very, very soon.

So I just looked at the new VP (who had just flown in from Kuala Lumpur) and said, "OK Hank (my boss), what do you want it to be?" he gave me a number something like 20% higher than mine. I smiled and said "I am sure that Koid (my successor) will have no problem hitting that number"

I am not sure what Koid thought, but that was his new target.

We had fun at these quarterly meetings. We introduced new selling techniques, new products, new marketing plans.

One other story from my last QSOR is that my boss asked who would like to introduce the marketing VP to the group. Nobody seemed too interested, so in the interest of fun, I volunteered to do so. She was so upset that right before I got on stage she came and asked me, sotto voce to please not embarrass her. Of course I did not. I gave a great introduction, stressing the importance of Marketing to the company (which I honestly believe, to this day)

Then I came home, took a couple of months off, and started with a brand new company.

That's up next.

Saturday, March 5, 2011

Landmark V, part two. So what exactly did you DO in Asia?

One of the themes of my career has been to seek out jobs that nobody else wanted. Or jobs that had no apparent route to success. My theory was that if you go to a place where everyone assumes you will fail, it will be easy to succeed. It has worked so far.

The APO group at Landmark had been under-performing the rest of Landmark for several years. The Company had replaced their long term VP (who coincidentally started the same day at Landmark that I did) with a fellow who was running a competitor's field offices in Asia. He hired many of his old friends, and worked diligently to try and change the Landmark culture into his previous company's culture. It did not work. There was an employee revolt, and he was let go.

I came to Asia where employee discontent was rampant. My first job was to reassure the people working there that their concerns were going to be taken seriously. I had several people ask me if my first action would be to fire them. (These conversations took place in the middle of the night for me, as I was still in Caracas). I let everyone know that I would make my personnel decisions based on performance, not on rumors.

Then I had to visit all the clients and let them know that the Company would continue to honor our commitments to them, and to make sure that they would be able to get their jobs done with our software. We made many more technical people available to help the clients, and we saw an increase in sales as a result. We increased sales 75% in a year, and profitability 105% in the same period.

The Company was also in the process of changing our business model to concentrate more on services, and less on product sales. We also reduced the responsibility of the regional VPs by moving marketing, pre-sales, and software support out of the regions in to global organizations. Some of the VPs were less than enthusiastic for these changes.

The Company did see an increase in sales during this period, though one would be hard pressed to say that there was an corresponding increase in profits.

But it did have the effect of making the Company more attractive as an acquisition target.

As I recall there were three companies that were interesting in purchasing Landmark. The end result was that Halliburton under Dick Cheney (yes, I met him) purchased the company.

I decided that HAL would not be the best thing for me, so I decided to leave the company.

So now it was time to move back to the US, and find something else interesting to pursue.

The APO group at Landmark had been under-performing the rest of Landmark for several years. The Company had replaced their long term VP (who coincidentally started the same day at Landmark that I did) with a fellow who was running a competitor's field offices in Asia. He hired many of his old friends, and worked diligently to try and change the Landmark culture into his previous company's culture. It did not work. There was an employee revolt, and he was let go.

I came to Asia where employee discontent was rampant. My first job was to reassure the people working there that their concerns were going to be taken seriously. I had several people ask me if my first action would be to fire them. (These conversations took place in the middle of the night for me, as I was still in Caracas). I let everyone know that I would make my personnel decisions based on performance, not on rumors.

Then I had to visit all the clients and let them know that the Company would continue to honor our commitments to them, and to make sure that they would be able to get their jobs done with our software. We made many more technical people available to help the clients, and we saw an increase in sales as a result. We increased sales 75% in a year, and profitability 105% in the same period.

The Company was also in the process of changing our business model to concentrate more on services, and less on product sales. We also reduced the responsibility of the regional VPs by moving marketing, pre-sales, and software support out of the regions in to global organizations. Some of the VPs were less than enthusiastic for these changes.

The Company did see an increase in sales during this period, though one would be hard pressed to say that there was an corresponding increase in profits.

But it did have the effect of making the Company more attractive as an acquisition target.

As I recall there were three companies that were interesting in purchasing Landmark. The end result was that Halliburton under Dick Cheney (yes, I met him) purchased the company.

I decided that HAL would not be the best thing for me, so I decided to leave the company.

So now it was time to move back to the US, and find something else interesting to pursue.

Monday, February 28, 2011

Landmark V, Moving to the other side of the world

In late 1994, the Vice President and General Manager for Landmark's Asia Pacific Organization (APO) was let go. I will leave the circumstances of that action to others more familiar with the situation. But it did open up a General Manager role in the Company, a role that I wanted.

To understand why this was an important position for the Company, it is important to understand the structure of Landmark at the time. We were probably about $100 million in sales, and the Company had three regions, or field operations, which were responsible for all client contract.

The largest of these (and the one I was part of for most of my career) was TAO, or The Americas Organization. Very descriptive - responsible for North and South America. I was responsible for the Latin American part - Mexico south.

Then there was EAME, or Europe, Africa, Middle East. You can probably figure out which part of the world they were responsible for. They had a new VP and GM who came from outside the oil industry. He had a good software background.

Then there was APO. Responsible for everything from Pakistan east to Japan, then Mongolia south to New Zealand. Lots and lots of miles.The headquarters for APO was in Singapore.

At that time (it was soon to change) each of the VP/GMs reported to the CEO and were officers of the Company. There were also VPs in charge of Software development, HR, and Legal. Each region was responsible for Sales, Support, Consulting, Training, and everything else that had anything to do with the clients

When asked if I wanted the job I said yes without hesitation. There were 71 people in the organization, much bigger than LAO (the Latin American Organization) and it had much higher sales. I would also be an officer of the Company (which brought with it some benefits such as a nice stock option package and an employment agreement)

So it was pack and pay time.

Moving from Caracas to Singapore was moving to the other side of the world both literally and figuratively. Singapore was a city based on rules, regulations, and a well ordered populace. Caracas was a city based on chaos. For example, in Caracas, nobody stopped at red lights, even in the middle of the day. In Singapore nobody ran red lights, even in the middle of the night.

We still had two dogs and two cats that had to be transported and quarantined before they could be set free on the unsuspecting Singaporean population. It was much easier getting them out of Venezuela than you could imagine, but then letting them sit in a cage for a month in Singapore was not fun.

But we did find an amazingly cool place to live:

The one behind the scaffolding

It was on Emerald Hill Road, just off of Orchard Road. Close to the MTA (subway) close to everything you would need.

There were covered walkways all over Singapore so you didn't have to walk in the rain:

supposedly Raffles created an ordinance that forced builders to include these walkways for pedestrians.

Here is another typical Peranikan Shop House:

Now, Singapore has be variously described as Disneyland with The Death Penalty, or A Shopping Mall that declared independence; but it was an easy place to live.

The malls were, indeed everywhere, and they were generally pretty nice:

It was hot, but cooler than Houston in July. That allowed for some great plants:

and more than anything else, the food was great:

Our office was on the 18th floor of Peninsula Plaza, and we had a great view of the anchorage:

And then there was the work.

This post is getting too long, so I will talk about the work next.

To understand why this was an important position for the Company, it is important to understand the structure of Landmark at the time. We were probably about $100 million in sales, and the Company had three regions, or field operations, which were responsible for all client contract.

The largest of these (and the one I was part of for most of my career) was TAO, or The Americas Organization. Very descriptive - responsible for North and South America. I was responsible for the Latin American part - Mexico south.

Then there was EAME, or Europe, Africa, Middle East. You can probably figure out which part of the world they were responsible for. They had a new VP and GM who came from outside the oil industry. He had a good software background.

Then there was APO. Responsible for everything from Pakistan east to Japan, then Mongolia south to New Zealand. Lots and lots of miles.The headquarters for APO was in Singapore.

At that time (it was soon to change) each of the VP/GMs reported to the CEO and were officers of the Company. There were also VPs in charge of Software development, HR, and Legal. Each region was responsible for Sales, Support, Consulting, Training, and everything else that had anything to do with the clients

When asked if I wanted the job I said yes without hesitation. There were 71 people in the organization, much bigger than LAO (the Latin American Organization) and it had much higher sales. I would also be an officer of the Company (which brought with it some benefits such as a nice stock option package and an employment agreement)

So it was pack and pay time.

Moving from Caracas to Singapore was moving to the other side of the world both literally and figuratively. Singapore was a city based on rules, regulations, and a well ordered populace. Caracas was a city based on chaos. For example, in Caracas, nobody stopped at red lights, even in the middle of the day. In Singapore nobody ran red lights, even in the middle of the night.

We still had two dogs and two cats that had to be transported and quarantined before they could be set free on the unsuspecting Singaporean population. It was much easier getting them out of Venezuela than you could imagine, but then letting them sit in a cage for a month in Singapore was not fun.

But we did find an amazingly cool place to live:

|

| From More Singapore |

It was on Emerald Hill Road, just off of Orchard Road. Close to the MTA (subway) close to everything you would need.

There were covered walkways all over Singapore so you didn't have to walk in the rain:

|

| From More Singapore |

supposedly Raffles created an ordinance that forced builders to include these walkways for pedestrians.

Here is another typical Peranikan Shop House:

|

| From More Singapore |

Now, Singapore has be variously described as Disneyland with The Death Penalty, or A Shopping Mall that declared independence; but it was an easy place to live.

The malls were, indeed everywhere, and they were generally pretty nice:

|

| From More Singapore |

It was hot, but cooler than Houston in July. That allowed for some great plants:

|

| From More Singapore |

and more than anything else, the food was great:

|

| From More Singapore |

|

| From More Singapore |

Our office was on the 18th floor of Peninsula Plaza, and we had a great view of the anchorage:

|

| From More Singapore |

And then there was the work.

This post is getting too long, so I will talk about the work next.

Monday, February 21, 2011

Landmark IV, Expatriated to Venezuela

In late December, 2002 1992 I was asked if I would be willing to move to Caracas and take over the sales operations for Latin America. I did not need to be asked twice. Careful readers of this blog may remember that I has already spent one summer in Latin America, and I reveled at the chance of getting back. I had the feeling it was not going to be an easy job, but I was very eager to take on such a challenge.

The first thing I had to do was find a replacement for myself. Remember, I said how hard and wearing the last post was, and I wanted to get someone who knew what they were getting themselves into. So I recruited our Canadian support manager to come down to Houston. He was originally reluctant, and his wife was not really completable in Houston. She though the crime rate was too high.

I pointed out that most crime in Houston is committed by someone you know, and since they didn't know anyone here, they would be safe. The pitch must have worked, because he took the job, they moved here and have stayed in Houston ever since.

Then I had to find a place to stay, sell my house, move, and get prepared for a job where I didn't speak the language, I wasn't really wanted, and the clients didn't trust us.

Starting from the top. I was able to sell the house at the last minute. It was a great house in the Houston Heights. I think I paid about $112k for the place, put a couple grand into it, and sold it for $150k five years later. Not a bad return, but not spectacular, either. I think it is now on the tax rolls for over $400k. (don't get too excited. It didn't even double twice in 20 years, so the appreciation would only be about 6% per year)

Our house in the Houston Heights

Finding a place to stay in Caracas was harder than you can imagine. We had two dogs and three cats, and contrary to most expat's preference, we wanted to live in a house. (Houses in Caracas we few and far between. They are harder to secure, and land was very expensive. They were called "fincas" (farms) instead of "casas")

We worked with a real estate lady named Natalie Bennecourt. We must have looked at 10 or 15 places until we found the one we wanted. It was in the "urbanizacion" )neighborhood) of Los Chorros (the waterfall) and was really the downstairs of a house built into a hill. We had our own yard, garage, services, and so on. The house did not come with any light fixtures. No, really - all the ceiling fixtures had been ripped out by the owners. (They had moved to Curacao as he worked for PDVSA as a ChemE in a refinery there)So we have to not only bring all our stuff, but buy light fixtures and ceiling fans to put in the house.

Quinta Mariguita, Av Las Magnolias, Los Chorros, Caracas

I liked that house, none the less. We had our own water tank, and our own well for when the city water was cut off. The yard was huge! We had avocado trees, mango trees, and passion fruit vines. We had exotic flowers that only opened at night. We had barbed wire around the top of the 10' wall.

Marina with the Night Blooming Cereus

I enjoyed working in Venezuela, even though, as I said above, they did NOT want me in the office.

Thinking about what I had to do at work

Drinking after I realize what I had to do at work

IT is hard to underestimate how unwelcome I was in Venezuela. The folks in the office (including, and perhaps especially, the expats) have been use to doing what they wanted with little oversight from Houston. I was viewed as that oversight. One of the Americans in the office said that he was going to pick me up at the airport on my house hunting trip. He decided to go to the beach, leaving me and my wife with no choice but to grab an airport taxi (highly discouraged) to the hotel. Nice guy.

The only person who tried to help me in those days was the office manager, and she remains a very dear friend. The person they had "running" the office was a Frenchman who did nothing more than put up roadblocks in my way. Thankfully, he was moved to Paris within a couple of months.

Coffee at the Office

The job was largely a series of meetings with clients around the region (I was responsible for everything Mexico and south. Originally it was only sales, shortly after I got there it was all operations as well) We had to rebuild a lot of relationships, and follow through on commitments made. This job was 100% about recovering broken relationships.

We must have been doing something right, as we double sales the first year, and then increased them by almost 70% the following year.

Even after my rocky start, I loved Venezuela. I looked at buying a coffee plantation:

but luckily did not close that deal.

Getting around in Venezuela was always interesting:

But I really enjoyed living there. This is getting to be a long post, but following are two letters I wrote back to my family after the first day I was there, and then after a month. We are all so infinitely adaptable!

The first thing I had to do was find a replacement for myself. Remember, I said how hard and wearing the last post was, and I wanted to get someone who knew what they were getting themselves into. So I recruited our Canadian support manager to come down to Houston. He was originally reluctant, and his wife was not really completable in Houston. She though the crime rate was too high.

I pointed out that most crime in Houston is committed by someone you know, and since they didn't know anyone here, they would be safe. The pitch must have worked, because he took the job, they moved here and have stayed in Houston ever since.

Then I had to find a place to stay, sell my house, move, and get prepared for a job where I didn't speak the language, I wasn't really wanted, and the clients didn't trust us.

Starting from the top. I was able to sell the house at the last minute. It was a great house in the Houston Heights. I think I paid about $112k for the place, put a couple grand into it, and sold it for $150k five years later. Not a bad return, but not spectacular, either. I think it is now on the tax rolls for over $400k. (don't get too excited. It didn't even double twice in 20 years, so the appreciation would only be about 6% per year)

|

| From Venezuela |

Finding a place to stay in Caracas was harder than you can imagine. We had two dogs and three cats, and contrary to most expat's preference, we wanted to live in a house. (Houses in Caracas we few and far between. They are harder to secure, and land was very expensive. They were called "fincas" (farms) instead of "casas")

We worked with a real estate lady named Natalie Bennecourt. We must have looked at 10 or 15 places until we found the one we wanted. It was in the "urbanizacion" )neighborhood) of Los Chorros (the waterfall) and was really the downstairs of a house built into a hill. We had our own yard, garage, services, and so on. The house did not come with any light fixtures. No, really - all the ceiling fixtures had been ripped out by the owners. (They had moved to Curacao as he worked for PDVSA as a ChemE in a refinery there)So we have to not only bring all our stuff, but buy light fixtures and ceiling fans to put in the house.

|

| From Venezuela 1993 |

I liked that house, none the less. We had our own water tank, and our own well for when the city water was cut off. The yard was huge! We had avocado trees, mango trees, and passion fruit vines. We had exotic flowers that only opened at night. We had barbed wire around the top of the 10' wall.

|

| From Venezuela 1993 |

I enjoyed working in Venezuela, even though, as I said above, they did NOT want me in the office.

|

| From Venezuela 1993 |

|

| From Venezuela 1993 |

IT is hard to underestimate how unwelcome I was in Venezuela. The folks in the office (including, and perhaps especially, the expats) have been use to doing what they wanted with little oversight from Houston. I was viewed as that oversight. One of the Americans in the office said that he was going to pick me up at the airport on my house hunting trip. He decided to go to the beach, leaving me and my wife with no choice but to grab an airport taxi (highly discouraged) to the hotel. Nice guy.

The only person who tried to help me in those days was the office manager, and she remains a very dear friend. The person they had "running" the office was a Frenchman who did nothing more than put up roadblocks in my way. Thankfully, he was moved to Paris within a couple of months.

|

| From Venezuela 1993 |

The job was largely a series of meetings with clients around the region (I was responsible for everything Mexico and south. Originally it was only sales, shortly after I got there it was all operations as well) We had to rebuild a lot of relationships, and follow through on commitments made. This job was 100% about recovering broken relationships.

We must have been doing something right, as we double sales the first year, and then increased them by almost 70% the following year.

Even after my rocky start, I loved Venezuela. I looked at buying a coffee plantation:

|

| From Venezuela 1993 |

but luckily did not close that deal.

Getting around in Venezuela was always interesting:

|

| From Venezuela 1993 |

|

| From Venezuela 1993 |

But I really enjoyed living there. This is getting to be a long post, but following are two letters I wrote back to my family after the first day I was there, and then after a month. We are all so infinitely adaptable!

April 16, 1993

Our first full day in Caracas comes to an early end. We have no furniture,

no TV, and no one to have a beer with but each other. The reality of being

2000 miles away from "home" is now taking hold. This is probably (my guess)

the worst time for a new assignment. Our stuff is not here, we really have

no friends, and we don't even know where to go fora quick beer after work.

As far as I can tell, most people in service jobs (working at grocery

stores, etc) hate them and their customers. I think that it is a reflection

of the early, easy wealth that oil generated in this country. If things

don't get done, it really is no problem, and if things start to look OK,

"Todo es Cheverre" (Everything is great) Coming from a continent, a

country, a state, and a family that places great store in personal

responsibility (well, I guess I am exaggerating some with the

continent,country, and state) it is a surprise to see people not taking any

responsibility for anything but their next day on the beach.

The trip down was long and tiring. We gave the dogs and cats to the kennel

service (they got all the paperwork for the pet done) at about 12:00 noon. We left the house at

about 1:30, and got to the airport at 2:10.

We had 4 huge dufflebags, two hanging bags, one box (small book box) and

the animals (two dogs and three cats) that we checked. We then had only my

briefcase, my computer, the boombox, our HUGE (usually

checked) suitcase, to carry-on. I think that

this will become the rule rather than the exception for international

travel (NO ONE was asked to check any of their stuff at the gate.). After

paying for excess baggage ($330) we made our way to the gate.We had a nice

two hour wait, ending with a teary goodbye with Joanne Gillock and her

baby, James.

The night before we left we had one last get together at 420 West 23rd

Street. Ree & Quinn, Bill & Joanne & James, and David Chandler were there.

It was very similar to many other evenings we had had before, except that

this one was the last. We had no furniture (Moving that stuff is another

whole story) so we sat on the floor and on borrowed chairs. We lasted until

about 11:00, and could take no more.

(NB: This is all being written while sitting on the patio,

since we have no chairs.) The first night here was mostly sleepless. I was

able to arrange for a mattress to be delivered to the house, and a short

one it is! We did not get settled until about 2:00 AM, and the the

unfamiliar noises (Jungle noises) tend to keep you awake.

I went to the office today for about 4 hours. I was told that it looks as

if we will not close some sales that had been forecast. In one day I feel

as if it is my chore here to shut down the Latin American organization. It

is only one day.

Our first day is drawing to a close. I realize that I know very little of

what I need to be successful here. My Spanish (which I was proud of 24

hours ago) is pitiful. I can't even ask a parking attendant for a parking

space! I know nothing of the clients or the culture. I don't know how to

buy groceries or get my shirts cleaned. I don't have a telephone book of

the yellow pages. I don't even have a three pronged outlet in my house.

If someone came to me right now and asked if I wanted to go home, I am not

sure what I would answer. I know that one day is no time to make decisions,

and I know that the learning is part of the adventure. I wanted to write

all this down because you only have one first day, and one time to record

them. I am sure that if I look at this even two weeks from now I will

laugh. At least I hope I will.

love,

dan

===============

===============

May 15, 1993

Dear All,

I am sitting on our Terrace drinking cafe maron, and typing this letter. What a difference a month makes. We received all of our furniture last week, I have my new company car (first one ever for me - and one of the few in Landmark), my Spanish is getting better poco a poco (little by little), and we are starting to know our way around the city. We (should) be getting our cable for TV installed today (English language TV), and we may even make a few sales this quarter. Keep your fingers crossed.

Did I mention that Puff took a powder? He left the first weekend we were here. We were hoping that he would come back, but it has been a month now, and no Puff. Too bad.

Last weekend we drove up the Avila (The mountain behind our house - a national park) to an old hotel (The Hotel Humboldt) that was built in the 50's by the last dictator. There was also a cable car that went from Caracas (elevation 900m) to the Hotel (elevation 2400m) and down to the Littoral (beach) (elevation 0m) The cable broke on the Caracas to Hotel leg about 10 years ago and they have not yet got it fixed. (They do not believe in preventive maintenance here). The hotel has been closed for many years as well - the only way you can get up is 4 wheel dive - but you can get tours. There are only 70 rooms, but what a great view. You can see the Caribbean on one side, and the city of Caracas on the other. Quite spectacular. The hotel looks like it was built in the 50's by a dictator. I ate an empanada from a vendor at the summit, and got sicker than a dog that night.

We drove down the other side of the Avila to the beach. I am not sure why people like to 4 wheel drive just for the fun of it. If you need to GET somewhere, that is one thing, but to do it for fun is too hard on my kidneys. the beaches look pretty nice. We didn't stay there too long.

The car I have is a new Jeep Cherokee Limited. It is kind of like Ree's car. I have only driven it from the dealer home - so I can't say too much about it. It is red wine colored, with fog lights, kangaroo bars, roof rack, and more. It has an alarm system, PLUS a padlock that locks the transmission in reverse, PLUS a lock that locks the brake and clutch together. (The insurance company will not insure it without the two padlocks) There is a kill switch on the alarm, as well as a special valet switch that lets the car run for about 15 minutes and then kills everything. (A flock of eight macaws just flew over the house.) It also has a fancy radio that may get stolen. This will be one of the vehicles that we use to drive down to the Amazon.

Some of our stuff was damaged in the move, but by and large it came through OK. I still think that we will sell almost everything we own down here and move very little. It is astounding how much stuff you can accumulate. We must have 100 glasses for example. I guess that is a result of staying in one place for a long time. I have reached the conclusion that it is better to have stocks than stuff.

Some of our stuff was damaged in the move, but by and large it came through OK. I still think that we will sell almost everything we own down here and move very little. It is astounding how much stuff you can accumulate. We must have 100 glasses for example. I guess that is a result of staying in one place for a long time. I have reached the conclusion that it is better to have stocks than stuff.

I now have my old computer set up, and we should have the house finished in another week or so. This moving stuff is for the birds. As I said above, and before, sell or give away all of your stuff. Life is simpler that way.

We may have our dedicated line between Houston and Caracas up next week. If so, I mat be able to get back on GEnie. That will be good if I can. Watch for more news.

Chau.

dan

Thursday, February 17, 2011

Landmark III, or: You call this SUPPORT???

The hardest job I ever held at Landmark was being the Customer Support Manager for North America.

It was hard for a number of reasons. One was the number of people that I had reporting to me, another was that we were reorganizing the way we provided support (and training, and pre-sales support to the sales force) yet a third was the general oil and gas environment at the time (not good).

We made some basic structural changes in the group while I was there. We decided to start specializing our support folks. Prior to this point, one person would be expected to take support calls one day, do a demo for a sales person the next, and then teach a training course of the software a week later. Sometime we would charge clients for these services, and sometimes we would not.

Now, folks generally don’t like change, but most of these changes were welcome in the group. We set up a “phone room” where all the support calls were routed and answered. We set up a dedicated training group and assigned Bill O’Brian (one of the nicest people I have ever worked with) to create a business. He hired, trained, sold, and created a cash flow stream where none existed before.

We had to hire so many trainers that we had whole recruiting campaigns were we would interview tens of people a day. We also “certified” out of work geoscientists whom we could then use in peak demand situations and pay people when we needed them.

We had some great trainers, and some interesting training stories from this group. One year Amoco had made an investment in an Albanian oil field. As part of their investment they bought a couple of workstations for the Albanian Geophysicists. We had to train them.

This was the first time there two fellows had been out of their country. They had no concept of an individual computer (imagine when you tell someone “Grab your mouse and click on “open” and you are greeted with blank stares. You go back to basics) nor much idea about how the US consumer culture worked.

Originally there were housed in a Hotel, but Amoco suggested that we put them up in an apartment, as it would be cheaper. When we took them to the apartment their eyes got big and they were very impressed. Then they were shocked when they realized that it was a two bedroom apartment, and they would not be sharing a bed!

When we took them to the grocery store it was like “Moscow on the Hudson” and they were amazed. But all they bought were potatoes. Lots of potatoes.

The idea of “on-site support” was also started during this time. Clients would pay to have one of our people go to their office every day, and they would pay us to make that happen. It was great for both sides, and really increased the utilization of the software.

But probably the worst part of the job was that Landmark released a version of its software named SeisWorks. Version one-point-oh came out on my watch. It was the worst software I have ever tried to use that was deemed “commercial”

We were under a lot of pressure to get this software delivered to meet some competitive threats. It was years in the making and would ultimate deliver some huge advantages for the clients.

But this was an example of software delivered way too soon.

And we in North American were the only group fool enough (or desperate enough) to deploy it.

From the minute it was installed it was a disaster. Nobody could keep it running for more that about 20 minutes without crashing.

MY favorite bug was one introduced because of a change in the underlying software language we used. In the old version, timing was measured in milliseconds. In the new, in seconds. But you can imagine the problems introduced if you didn’t know that. Suddenly the software was apparently hanging when it was really just waiting for time to pass. There was a clever solution we found, however. If you moved the mouse continuously, the timing loop would be skipped. We called it “Mouse Pumping” (and is surprising useful in much software today! Try it sometime when it looks like your software is slow or frozen)

During that time I never got one phone call from a client telling me what a great job the Company was doing. I spent a real lot of my time on sales calls trying to explain what we were going to do better, and how soon we were going to do it better. It was a tough time.

Ultimately, though, the Company did step up. We created a hit team and prioritized the bugs, fixed them, and delivered the product we should have delivered in the first place. There is a huge lesson I still carry with me to this day about this. Do the job right. It is cheaper and faster than doing it again.

Wednesday, February 16, 2011

Landmark II, moving up in the world

I was a Landmark salesman for 18 months. A good 18 months that taught me a lot about how to talk to clients, present value propositions, close business, and understand that listening to clients was much more valuable than talking to clients.'

But something else much more important happened to me in that 18 months. I met by sweet ever lovin' wife there. We did not "see" each other while working together. As a matter or fact, we were even married to others. But that is how we met, and above all else, for that I am grateful to Landmark Graphics.

But let's get back to work.

The reason that I was a salesman for only 18 months is that Landmark had a wholesale management change at that point. My boss (Laura, mentioned earlier) and Richard (also mentioned earlier) were politely asked to pursue other interests. They did, and a fellow named Larry White was hired from Schlumberger (the new President's old company) to run the North American region.

It was apparent that Larry needed some help with the sales folks, so I approached him and said that I could act as his Sales Manager while he searched for the perfect candidate. He was a little reluctant at first, but soon saw the wisdom of such and approach. I kept one account for a short period (you can't serve two masters) and then starting being a sales manager.

Which reminds me of a joke:

A guy goes hunting and wants to hire a dog to retrieve the catch.

"I have just the dog for you, sir." says the gamekeeper. "He's called Salesman and he is brilliant" Off they go and every time the hunter shoots a bird the dog runs off and brings the bird back just as he was hired to do; a great success.

The following year, the same guy goes back and asks for Salesman as he was so good last year.

"Ah, I'm sorry, sir, but it won't work anymore. Someone had the bright idea of calling him Sales Manager - now he just sits on the porch and barks all day".

I worked as the Sales Manager for a year, but in that year hired two of the best salesmen that Landmark ever saw. Heck, two of the best salesmen that I have ever seen work. They made my job much easier as a manager.

Once you have been in sales, and once you have managed sales people, I believe that you can do just about anything you put your mind to.

We started an industry, and now we were kicking it into the real world.

My next job (and next post) was one of the most thankless positions I even held. Manager of Customer Support for North America.

But something else much more important happened to me in that 18 months. I met by sweet ever lovin' wife there. We did not "see" each other while working together. As a matter or fact, we were even married to others. But that is how we met, and above all else, for that I am grateful to Landmark Graphics.

But let's get back to work.

The reason that I was a salesman for only 18 months is that Landmark had a wholesale management change at that point. My boss (Laura, mentioned earlier) and Richard (also mentioned earlier) were politely asked to pursue other interests. They did, and a fellow named Larry White was hired from Schlumberger (the new President's old company) to run the North American region.

It was apparent that Larry needed some help with the sales folks, so I approached him and said that I could act as his Sales Manager while he searched for the perfect candidate. He was a little reluctant at first, but soon saw the wisdom of such and approach. I kept one account for a short period (you can't serve two masters) and then starting being a sales manager.

Which reminds me of a joke:

A guy goes hunting and wants to hire a dog to retrieve the catch.

"I have just the dog for you, sir." says the gamekeeper. "He's called Salesman and he is brilliant" Off they go and every time the hunter shoots a bird the dog runs off and brings the bird back just as he was hired to do; a great success.

The following year, the same guy goes back and asks for Salesman as he was so good last year.

"Ah, I'm sorry, sir, but it won't work anymore. Someone had the bright idea of calling him Sales Manager - now he just sits on the porch and barks all day".

I worked as the Sales Manager for a year, but in that year hired two of the best salesmen that Landmark ever saw. Heck, two of the best salesmen that I have ever seen work. They made my job much easier as a manager.

Once you have been in sales, and once you have managed sales people, I believe that you can do just about anything you put your mind to.

We started an industry, and now we were kicking it into the real world.

My next job (and next post) was one of the most thankless positions I even held. Manager of Customer Support for North America.

Monday, February 14, 2011

Hitting the Big Time. Landmark Graphics calls.

Landmark Graphics is one of the big success stories in Houston High Tech history. They were founded in 1982, went public in 1988, and sold out to Halliburton in 1996. I was fortunate enough to be part of that ride. I will break this portion of my story into five parts - I had five separate roles while there - and talk about each.

As I mentioned before, Landmark resold some of the software that Terra-Mar wrote (or acquired). I had developed a pretty good relationship with the LGC guys, even interviewing them for a Product Manager position for one of their new products.

That didn't pan out, but in 1989 they made me an offer I could not refuse. I was hired by Laura Capper to become one of a select group - a Landmark Salesman. Now, this was a plumb position back in those days. They give you lots of flexibility, and if you sold the stuff (not an easy job, but very sell-able) you could make good money. As a matter of fact, the Sales VP- Richard Barren (Laura's Boss) told me that ALL the North American salesmen made over six figures. That was big scratch for a 32 year old who was equity heavy but liquidity light. I took the job and it was the best decision I have ever made.

I sold the products for about 18 months, and in that time got to know the entire management team, all the developers, and most of the company. When I joined there were 135 people and we had about $35 million in sales. You had access to everyone at the Company, and most every oil company executive as well.

Our main competition had some good software, but it was not as good as ours. They had some good people, but they were incented differently. We were paid a very low base and an aggressive commission. The competition was paid a high base and not much of a commission at all. They were prone to using discounts to get sales, we scorned discounts. It was sort of a free-for-all, as we were plowing virgin ground.

Landmark not only had to sell the software used to interpret 3D seismic, but frequently had to convince the oil companies to use 3D seismic at all. The oil industry is sometimes reluctant to use new technologies, and even something as obviously beneficial as 3D seismic took a long time to gain acceptance.

But we had the right people at the top (selling to oil companies, and perhaps more importantly - banks) in the middle (managers who knew how to get things done) and at the bottom (the salesmen, support people, and developers - all who had a passion for the company and the product).

Not that we didn't have some very debilitating personnel issues! We all drank too much, fought too hard, and played too rough. I don't think that we (any of us) could get away with what we did back then.

But that is where many of us grew up. Every ex-Landmarker wears that title like a badge of honor. And for me, it started in the field, carrying a bag.

As I mentioned before, Landmark resold some of the software that Terra-Mar wrote (or acquired). I had developed a pretty good relationship with the LGC guys, even interviewing them for a Product Manager position for one of their new products.

That didn't pan out, but in 1989 they made me an offer I could not refuse. I was hired by Laura Capper to become one of a select group - a Landmark Salesman. Now, this was a plumb position back in those days. They give you lots of flexibility, and if you sold the stuff (not an easy job, but very sell-able) you could make good money. As a matter of fact, the Sales VP- Richard Barren (Laura's Boss) told me that ALL the North American salesmen made over six figures. That was big scratch for a 32 year old who was equity heavy but liquidity light. I took the job and it was the best decision I have ever made.

I sold the products for about 18 months, and in that time got to know the entire management team, all the developers, and most of the company. When I joined there were 135 people and we had about $35 million in sales. You had access to everyone at the Company, and most every oil company executive as well.

Our main competition had some good software, but it was not as good as ours. They had some good people, but they were incented differently. We were paid a very low base and an aggressive commission. The competition was paid a high base and not much of a commission at all. They were prone to using discounts to get sales, we scorned discounts. It was sort of a free-for-all, as we were plowing virgin ground.

Landmark not only had to sell the software used to interpret 3D seismic, but frequently had to convince the oil companies to use 3D seismic at all. The oil industry is sometimes reluctant to use new technologies, and even something as obviously beneficial as 3D seismic took a long time to gain acceptance.

But we had the right people at the top (selling to oil companies, and perhaps more importantly - banks) in the middle (managers who knew how to get things done) and at the bottom (the salesmen, support people, and developers - all who had a passion for the company and the product).

Not that we didn't have some very debilitating personnel issues! We all drank too much, fought too hard, and played too rough. I don't think that we (any of us) could get away with what we did back then.

But that is where many of us grew up. Every ex-Landmarker wears that title like a badge of honor. And for me, it started in the field, carrying a bag.

Saturday, February 5, 2011

Smaller still, a new start-up

DPC&A and I parted ways in 1986. I pursued a couple of ideas somewhat halfheartedly (I wanted to set up a Multi-Level Marketing computer sales company, and even registered a name and started some market research. Did you know that you can buy mailing lists of people in a given zip-code with children in grade school? With Phone numbers? Call them once to see how interested they are in owning computers. In 1986 the answer was, "Not so much") but my real goal was to go to work for a small (2 people!) software company called Terr-Mar Resource Information Services.

And so I did.

We sold a PC based Satellite image processing system. This was before PCs were really quite capable of such things. We have to do a lot of hardware modification, and plenty of software modification as well. The only way to get the data into the computer was to use a 9-track (those big round tapes) tape drive that was not really conducive to a PC. The only way to manipulate the data was to put it into a "framebuffer" which allowed you very fast processing. It all worked, but just barely. I spent a lot of time inside of computers.

The company was headquartered in Mountain View, CA. It was a great time to be flying out to Silicon Valley. If I would have known then when I know now, that would have been a great time to move to The Valley and dedicate myself to the software world. Instead, I stayed here in Houston and dedicated myself to the Oil and Gas world. I don't regret it, (road not taken, and all that) but I occasionally wonder how different my life would have been.

About a year into Terra-Mar, we stumbled across a local software company called GeoSim. This was a life altering connection for me.

We acquired GeoSim for no money from a fellow named Steve Nightingale. GeoSim wrote software that was used to help interpret seismic data. It, too, was PC based. Steve's family owned the Cal Neva casino in Reno, and this company was a diversification for them.

GeoSim wasn't doing so well (not that we were, either) so Terra-Mar took over GeoSim and no money changed hands. But this got us into a much bigger field with much bigger players.

(one part of that field was Reno. More than one of our Board Meetings were at the casino. It was like a movie. After one of our meals we had the opportunity to sample the "cognac cart". I chose a Hines cognac that was $50/glass. In 1987 or so. Here is my take away from that interaction. Don't piss off gaming lawyers)

Landmark Graphics, at the time little more than a start-up themselves, resold the GeoSim software. This was my first introduction to the company that would make a really big impact on my career.

I ran the Houston office of Terra-Mar for three years. It was apparent at that time that we did not have the capital to make the jump to the big time. Landmark had been recruiting me for a while, so I make the decision to leave. It was not an easy one, but it was a lucrative one.

And so I did.