So now I needed to find another job.

Exxon Minerals wanted to make me a DataBase administrator, as I intimated in my last post. But I knew better - I wanted to be an Engineer.

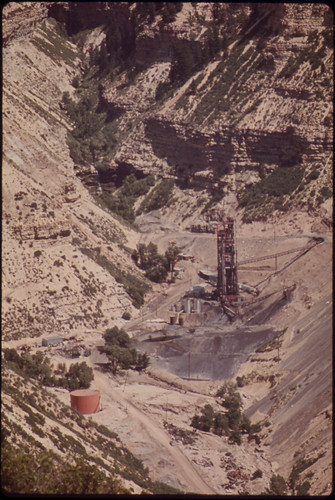

So I called up the head of HR for the Colony Project. Colony was one of the big oil shale projects going on at the time:

Oil Shale (a misnomer. It has kerogen, not oil, and it was a marlstone, not shale) was a messy expensive way to get a liquid hydrocarbon. The highest grade shale we had was about 1 bbl/ton. That is right, about one barrel of oil per ton of rock. That meant that in order to produce the 50,000 bbl per day we were planning on we would have to process almost 70,000 tons of shale.

The capital cost for that project was going to be about $5 billion. Even a cursory glance at the economics shows that is not a good deal. So I should not have been (and indeed, wasn't) surprised about a year later when the inevitable happened.

In the meantime, however, I had a great time.

I was responsible for a couple of things - one was the selection of roof bolters:

|

| From Some Old Photos scanned 10.29.05 |

|

| From Some Old Photos scanned 10.29.05 |

These machines place "resin" bolts into the roof to help maintain its integrity. (ie, so it won't fall down). You would drill a hole,. stick a tube with an epoxy like paste inside (a plastic tube with two components that would remain soft when separate, but would harden when mixed together), then stick a pieces of rebar into the hole and spin it. You then press it against the roof with a header board (a 2x4) and let it set for about 30 seconds.

I was also responsible for getting the mine layout into the computer. This was 1981 remember, so it was a mainframe computer located in Houston - and we were in Denver. It was a painstaking exercise that never really worked out that well.

In the end, the mine was canceled. Probably a good thing, too. There would have been all sorts of deleterious environmental consequences to that mine. Water, dust, people.

I enjoyed living in Denver for that year, but fate would bring me back to Houston next.